San Pedro Daily Breeze, August 6, 2004

60 YEARS LATER, WWII INTERNMENT CAMP SURVIVORS REUNITE

By Dennis Lim

MORE SAN PEDRO

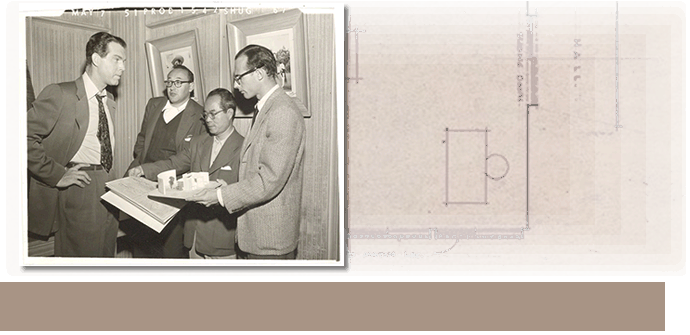

For nearly 60 years, Hideo Endo and Chiyo Nakahara hadn’t seen, heard or talked to each other.

Tossed into a World War II internment camp more than a half century ago, the pair shared friendship and hardship through one of the darker chapters in this country’s history.

Neither knew each other before their detention.

Endo grew up in San Pedro, the son of a fishing barge captain. Nakahara came from Inglewood.

During their incarceration, they were placed in wooden shacks across from one another.

Through mutual friends, the two met—Nakahara’s future husband, also at the camp, went to San Pedro High School with Endo.

With differing interests and separated by seven years of age, the two never developed the strongest of friendships, but they did notice each other.

From her porch, Nakahara watched Endo as he went on dates.

Endo always made it a point to say hello to Nakahara when he saw her.

But after the war, the two separated and developed separate lives.

They never saw each other again until March, when they accidentally met in San Pedro.

Endo moved into the Harbor Terrace Retirement Community where Nakahara lived.

“It was nice to hear a friendly voice,” Nakahara said. “I was very surprised to see him here.”

Endo agreed.

“It was nice to have a familiar face in a place like this,” said Endo about moving to a new, unfamiliar home.

At eight-eight years old, Endo’s short-term memory has suffered with age.

Still not the closest of friends, when the pair do talk, they reminisce about their time at the Arkansas camp.

A lot of the time they ask one another what happened to people that were there.

Most have died.

Many moved to Hawaii after the war and still live there.

The rest have scattered across the country.

Fearful of espionage after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed an executive order in 1942 to remove all people of Japanese ancestry from the western United States of America.

Many of them, like Endo, had lived in America their entire life and had no reason to be suspected of espionage.

Roosevelt’s order uprooted more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans from their homes with only the possessions they could carry.

In 1988, Congress issued a national apology to the Japanese-American community and offered $20,000 in reparations to those interned.

Both Endo and Nakahara expressed mixed emotions about the internment experience.

“After a while, it got very boring,” Endo said. “Our life was put on hold for a couple of years.”

“It was very rough,” Nakahara added. “No one could understand it. We were born here. We had relatives in the army. We just couldn’t understand why we were there.”